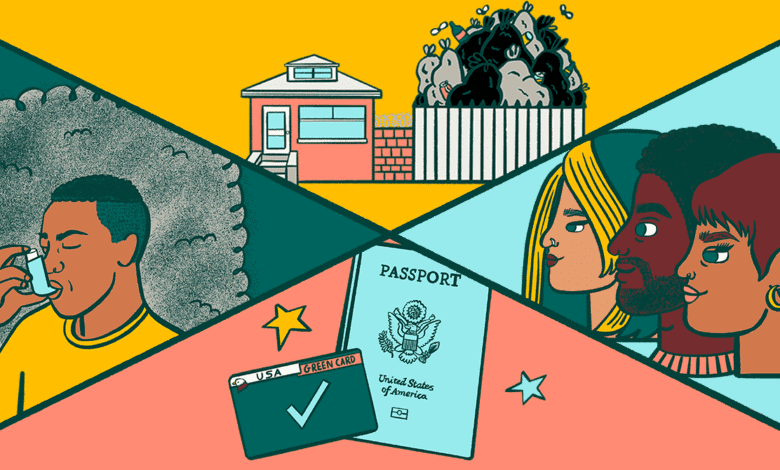

Intersectional Environmentalism: EXPLAINED

Disclaimer: The purpose of this essay is to provide a general overview of the numerous subjects that belong under the banner of Intersectional Environmentalism and Environmental Justice. We want to delve into further depth on the many issues covered in this post in the future, but for now, we hope you’ll use this article as a reference to understand the concepts and a chance to become acquainted with the terminology.

It’s no secret that the globe is on fire right now, with more and more individuals standing up against prejudice in their neighborhoods and on a worldwide scale. As more people are called out for perpetuating racism or failing to actively advocate for those who are disproportionately affected by it, the mainstream debate is evolving.

You may be wondering, “How can I fit into this movement?” if you are interested in environmentalism and the health of the earth. Hence, we advise you to utilize this essay as a starting point for deconstructing and comprehending the notion of Intersectional Environmentalism and how to apply it into your activism.

This brief article will provide a high-level explanation of what Intersectional Environmentalism is, who it relates to, and how it works. We’ll discuss the various terms and language commonly associated with this discussion, the connection between social justice and environmentalism, the exclusion and/or misrepresentation of BIPOC people and POC in climate discussions, wealth and equalities, and, finally, how using a variety of perspectives on this subject can help you better understand it in its entirety.

“This is an inclusive type of environmentalism that argues for both the protection of people and the conservation of the world. It examines how injustices against disadvantaged populations and the environment are linked. It puts to light injustices against the most vulnerable groups and the environment, rather than minimizing or silencing socioeconomic inequalities. Intersectional Environmentalism seeks justice for both people and the environment.”

Intersectional Environmentalism, as defined by S. Ryder, is a link between Feminist and Gender Studies and Environmental Studies. This idea is based on the term Intersectionality, which was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1991 and states that individuals may be oppressed and differently influenced by “a variety of interrelated social institutions” based on their identification features. These structures are divided into several categories, including, but not limited to, race, gender, sexuality, ability, and class.

Intersectionality has been spoken around a lot recently, particularly in the last 5-8 years, therefore we felt it would be beneficial to provide a simple description.

Intersectionality is frequently utilized as a lens through which to examine certain institutions or societal problems in our environment. Hence, while determining whether anything is Intersectional, ask yourself if what you’re looking at employs a broad-spectrum understanding concerning the unique experiences of different types of individuals.

You may be wondering what a worldview is. Simply expressed, it is the process through which you, as a person, form your worldview based on your life experiences and the circumstances in which you grew up. It also has to do with the many concepts you were and are exposed to during your life.

The basic idea of this piece and this larger topic is that humans and the environment cannot be separated. To attain Intersectional Environmentalism, you must examine concerns such as climate change, environmental degradation, and deforestation from an intersectional perspective. They are never merely environmental concerns.

Lauren Singer, the creator of Trash Is for Tossers and Package Free Shop, was chastised in 2018 for her lack of intersectionality in an Instagram post promoting the accessibility of a Zero Waste Living for all. “We have an issue when someone’s advocacy overlooks intersectionality,” writes Ethical Unicorn (2018).

The effort to prohibit single-use plastic straws is a simple example that exemplifies this principle perfectly. This movement is clearly the most capable since it overlooks people who require such a gadget to eat.

Not everyone can pick up a cup or glass, and metal/glass straws are not always an acceptable substitute due to their hardness. This example demonstrates how environmentalism alone does not always take into account how certain environmentally friendly initiatives might exclude others who do not have the same advantages.

Veganism is another environmental movement that frequently has similar one-sided viewpoints. Veganism, particularly in online environments, has evolved a “militant” tone, as Rylee McCallin describes.

These “militant vegans” make a point of condemning any behaviour associated with or linked to the eating of animal products in the name of preserving the world and protecting animals. This popular cliché also tends to disregard historical and cultural practices associated with the eating and usage of animal products in communities of colour.

Several indigenous voices, like Kima Nieves and Linda Fisher, have highlighted the overt anti-Indigeneity that comes with these misguided judgments. A issue that is sometimes overlooked in these debates is that the pictures of mass killing, and environmental damage depicted in documentaries such as Cowspiracy and Forks Over Knives are visuals associated with industrial farming.

Factory farming is a large-scale commercial venture that differs from the more traditional small-scale, community-level hunting and animal husbandry practiced by many Indigenous and other communities of colour.

People are brutally judged and misunderstood when they lack an Intersectional viewpoint on these issues. There is no one “correct method” to save the earth, and understanding this requires knowing about and interacting with various approaches. Solitary voices should never speak for what is meant to be a collaborative movement.

But hold on, there’s more…

Environmental activism is also extremely white. Anna’s Voice (2018) points out that “the leaders of the movement, the individuals who I see in environmental areas, and the ones who get all the limelight for their activism are frequently white and rich”.

Vanessa Nakate, a famous Ugandan teenage climate activist, was cut out of an Associated Press photo of Greta Thunberg and three other members of the Fridays for Future campaign shot during the World Economic Forum.

For decades, Black and Indigenous activists have sponsored several powerful and long-lasting environmental movements, yet their voices are frequently ignored. Their issues and experiences are “othered” since they have no bearing on the dominant white group.

It appears that white activists only acquire traction and attention when they join the movement and begin speaking out against the same concerns.

It is critical to recognize that the rich global 1% are responsible for the great bulk of environmental harm. We’re talking about multinational corporations, labour exporting, and globalized industries. As a result of these economic frameworks, climate change, environmental degradation, and pollution disproportionately harm Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour.

It’s not a surprise that the world’s impoverished tend to be racialized. Colonialism and capitalism have resulted in a profoundly uneven distribution of wealth and exclusion. Because of this history, communities of colour are disproportionately vulnerable to environmental health concerns.

According to Leah Thomas’ article Intersectional Environmentalism: Why Environmental Justice Is Essential for A Sustainable Future, “minority and low-income communities were statistically more likely to live in neighbourhoods exposed to toxic waste, landfills, highways, and other environmental hazards.”

Furthermore, when these groups speak out against injustice, they are frequently disregarded or dismissed. This is why we see so many of the same battles repeated year after year with little change.

More than 100 Indigenous reserves in Canada lack access to safe drinking water; Flint, Michigan, is entering its seventh year without safe drinking water; and Indigenous peoples in Brazil are being forced out of their lands due to rapid deforestation facilitated by a government that disregards their land claims. Without an intersectional perspective, none of these environmental challenges can be investigated.

While brainstorming tactics to counteract the consequences of climate change and create a higher regard for the world, it is critical to actively endeavour to employ various and distinct methodologies and beliefs. Recently, a lot more effort has been placed into listening to various Indigenous peoples to gather their thoughts on how we may better our work.

But, as pointed out by Leddy (2017) in his article Intersections of Indigenous and Environmental History in Canada, “there is a clear dichotomy in the realm of [Traditional Ecological Knowledge] TEK that needs to be understood: there is an Aboriginal view. . .and there is the dominant Eurocentric view of TEK, which reflects colonial attitudes toward Aboriginal people and their knowledge”.

As a result, respecting and employing ideas from other worldviews helps us to generate fresh perspectives and reorient ourselves in our understanding of societal challenges. There is no universal “correct approach,” and seeking to impose it actively dismisses and excludes people from the cause.

If we, as a group of environmental activists, are to accomplish meaningful and long-term change, we must take an intersectional strategy. Without an intersectional strategy, “activists may think they’re advancing towards meaningful social change, but they’re really just producing progress for a very tiny, very limited group of individuals,” according to Ethical Unicorn.

This essay may have given a bleak picture, but don’t worry; there are several actions you and your community can do to make environmentalism more intersectional. It begins withstanding up to injustices and elevating the voices of people who are touched by them.

This may be accomplished through participating in protests and rallies, signing petitions, and sharing information with friends, classmates, and co-workers. It is also possible to hold your elected authorities responsible.